It Started with a Druid and a Nun Having a Conversation*

An author describes how a historical fiction series grew out of a single image

The start of the story that turned into a saga—and one which took over more of my life than I ever intended it to—was an image that came to me when I was toying with the idea of writing a medieval murder mystery.

I did not have a particular plot or an exact time in mind, but pictured a tall, dark-haired Druid and a short, nervous nun having a conversation in a small underground chamber. While I didn’t yet have any idea why they were there or what they were talking about, I was certain that the nun was Saxon and that the chamber was underneath a Christian shrine. Those “facts” set the story’s timeframe, fixing it between the completion of the Saxon conversion to Christianity in the late 600s and the Viking invasions that began a century later—something I can say now, although I will also say that I began this work with what was at best a sketchy understanding of early British history.

I was curious about who these two people were, why they were in the chamber, and what happened to them after that.

Rather than being taken up with the big picture of characters contending with ethnic and religious conflicts in the Middle Ages, I was curious about who these two people were, why they were in the chamber, and what happened to them after that. Somehow it seemed that the only way to find out was to start writing, so I spent the next several months dashing off what was to become the Druid Chronicle’s first draft and didn’t begin any serious research into the period until I knew how things came out.

At that point I put the manuscript’s draft aside, and started to read whatever I could find at the library, in my local bookstore and on-line about Celts and Saxons, life in monasteries and convents, medieval farming and folktales, cooking over firepits and treating medical problems with herbs and incantations, as well as accounts of the Anglo-Saxon takeover of what is now England by writers on both sides of that struggle.

. . .to understand the people I envisioned as living in a hidden valley and continuing to practice a pre-Christian, polytheistic religion, I had to go back to the European Iron Age

While the Anglo-Saxon period is generally counted as starting with the withdrawal of Roman forces at the end of the fourth century and ending with the Norman invasion in 1066, it quickly became apparent that to understand the people I envisioned as living in a hidden valley and continuing to practice a pre-Christian, polytheistic religion, I had to go back to the European Iron Age, a period during which our understanding of Celtic culture relies on a mix of archaeology, linguistics, and a limited number of accounts by foreign commentators. Then, in order to have a plausible explanation for how the small outcast cult could have sustained itself over the eight centuries between the last report of a Druidic center in the first century AD and the time of my “chronicles,” I needed to gain a reasonable grasp on the subsequent Romano-British and Anglo-Saxon periods, including the conversion first of the native Britons and later of the Saxon kingdoms to Christianity.

I traveled to the United Kingdom with my husband and the Ordnance Survey map of ancient monuments in Great Britain, Scotland and Wales.

It was during this phase of my research that I traveled to the United Kingdom with my husband and the Ordnance Survey map of ancient monuments in Great Britain, Scotland and Wales. Already entranced by the early history and archeology of the British Isles, we started each of three trips at the British Museum. Then we rented a car, unfolded our map, and set out across country, taking in several of the well-maintained and highly informative heritage sites—including the awe-inspiring Stonehenge—but also following back roads, stopping at local museums in small towns with amazing displays of finds from nearby excavations, and taking advantage of the UK’s system of public access walkways to visit the vestiges of iron age hill forts or secluded standing stones in the company of grazing sheep. Beyond the wealth of knowledge gained from those trips, we had the experience of sitting in a pub in northern Wales and hearing teenagers in a nearby booth talking to each other in one of the oldest extant languages in Europe.

Beyond the wealth of knowledge gained from those trips, we had the experience of sitting in a pub in northern Wales and hearing teenagers in a nearby booth talking to each other in one of the oldest extant languages in Europe.

The reason that I didn’t do the historical research before I wrote the first draft was fear that the vibrancy I sensed in those two characters might not survive the rigors of dry documents and academic controversies. While I still think I made the right decision, the opportunity to immerse myself in the richness of a past age accounts for whatever depth and color I have been able to instill in their story.

*Originally posted in Reading the Past June 15, 2021

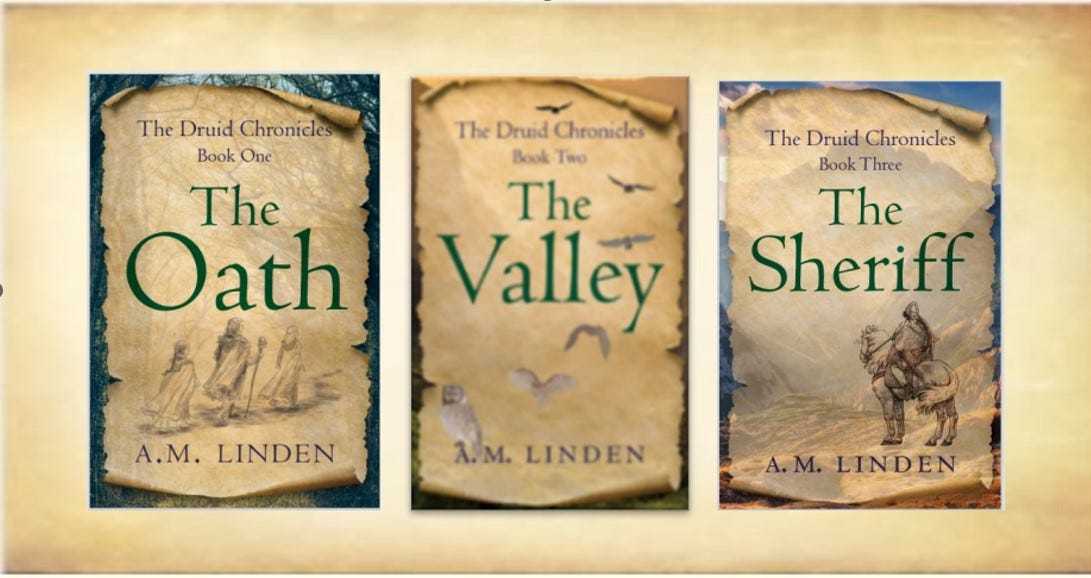

Author’s Note: While the books in The Druid Chronicles are available at all major book sellers, I encourage readers to patronize their local book store or, if unavailable there, to consider purchase through Bookshop.org.

It’s so good to be learning the journey that enriched your books.

Dear Margaret, I know have such a better understanding of how the writing of your books came about. How wonderful that you were able to travel and do the research. Your books are definitely historical in nature. History is best learned through stories of those living in those times. Your books are wonderful!